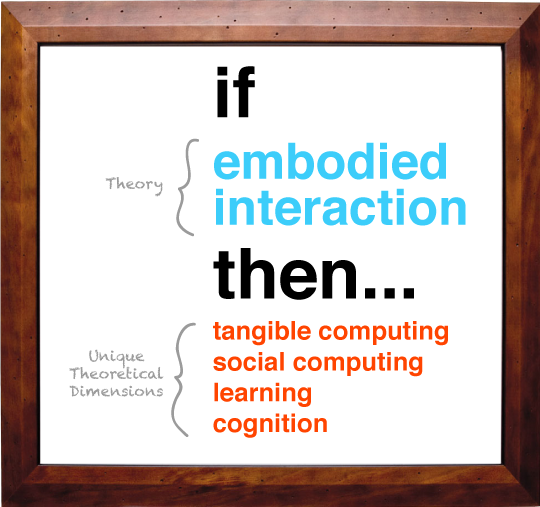

IF THIS THEN THEORY

Introduction

Embodied interaction suggests that we should view technology not just as a series of mental interactions, but also as physical interactions. As Dourish (2001) puts it, “Embodied Interaction is interaction with computer systems that occupy our world, a world of physical and social reality, and that exploit this fact in how they interact with us.” Dourish also references “Tangible Computing,” a term that means several different computational devices responding to each other as their location in the physical world changes. These computational devices can be computers as we generally think of them (laptops, printers, phones, etc.), but they can also be everyday things that have been augmented with computational power (paper, furniture, clothes, etc.). Tangible computing in the extreme would mean that anything you interact with could have an effect on your data and we would no longer need a mouse or GUI. Embodied interaction also looks at how technologies can create “Social Computing,” which is “…to incorporate understandings of the social world into interactive systems.” (Dourish, 2001).

Tangible Computing

Using the lens of tangible computing we can see that IFTTT fits into embodied interaction fairly well. IFTTT encourages users to create interactions using not only their physical location in the world, but also by using the location and physicality of other objects in the world. To program these interactions, one must still conform to standard interactions with a standard iOS GUI, however, once the interactions are defined, the user can use the physical environment as controls. For example, Joe can use his physical location in the world as a trigger for an interaction. Setting up a recipe in IFTTT can use leaving work to go home as a way to interact with Joe’s lights in his garage (using a combination of the Maps app and the WeMo light switch). IFTTT currently resides primarily on a desktop and mobile platform, and is therefore limited to interactions between apps, however one can imagine a more sophisticated version of IFTTT that would allow more complex interactions. What if Joe could program a recipe that would send him an SMS telling him to finish his homework when his Xbox gets turned on? One could imagine an example of tangible computing in a recipe that would start playing Joe’s “Cooking Jams” playlist and start pre-heating the oven at 350 when he takes the roast out of his fridge.

Social Computing

IFTTT also has aspects of social computing. Recipes can use social events as triggers for other social events. IFTTT can also combine tangible computing and social computing to create social interactions based on physical things in the world. Joe can build on his recipe of leaving work to interact with his team by letting them know what his schedule is for the next day. Joe can also use his physical location as a trigger to send a message to his partner alerting them he is on his way home. Breaking from the example of leaving work, a more concrete example of social computing would be a recipe that would monitor Joe’s Twitter followers and if ten or more start following the same new Twitter user, then Joe starts following that twitter user as well.

Learning

Embodied interaction alludes to something else we can look at in IFTTT, learning. Seeing things in the physical world can help us learn faster. Klemmer, et al. (2006) refer to this as “learning through doing.” While embodied interaction can get us started thinking about learning through doing, activity theory can guide us through the process. Leontiev (1981), gives an example of an infant learning to use a spoon through a series of activities. If we looked at learning in IFTTT using embodied interaction and activity theory together, we could say that as users made recipes in IFTTT, they would get better at incorporating more objects in the world, more social interaction tools. This could lead to creating complex chains of recipes that would become more and more useful as the user learned more strategies.

Cognition

Embodied interaction does not give us a view as to why a user might want to do these tasks, distributing their cognitive load, for example. It also does not give us a very good tool for examining recipes that don’t fall under tangible or social computing, even though these recipes might be useful and important. However, embodied interaction does let us look at IFTTT in terms of physical embodiment and social interactions. We can evaluate current recipe options using the lenses of social and tangible computing, and we can look to the future and imagine options for new recipes.

![]()

References

Dourish, P. (2001) Where the Action Is: The Foundations of Embodied Interaction. MIT Press, Cambridge.

Klemmer, S. R., Hartmann, B., & Takayama, L. (2006, June). How bodies matter: five themes for interaction design. In Proceedings of the 6th conference on Designing Interactive systems (pp. 140-149). ACM.

Leontiev, A.N. (1981) Problems of the Development of Mind. Progress, Moscow.

IfThisThenTheory.com | An HCDE 501 Site