IF THIS THEN THEORY

Introduction

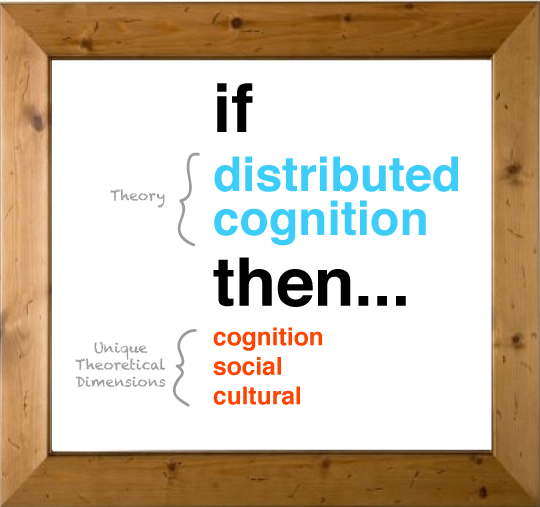

In this portion of the website, we will examine Joe’s interactions with IFTTT through the distributive cognitive lens. The authors of “Distributed Cognition: Toward a New Foundation for Human-Computer Interaction Research” note that distributed cognition is able to examine cognitive processes that are both internal and external, including cognition that is distributed socially as well as distributed through time and space (Hollan, Hutchins, & Kirsh, 2000). Through distributed cognition, researchers are able to look at cognitive systems through either high-level or low-level analyses, which are defined based on the types of research questions and the situations being examined (Rogers, 2012).

Cognition

The idea that objects and materials become a part of the user in their daily life is a key component of distributed cognition. Hollan et al. note, “Work materials from time to time become elements of the cognitive system itself.” (Hollan, et al., 2000). It is easy to see how IFTTT can become ingrained in the life of its user because it automates many functions that are easy to do, but often even easier to forget.

For instance, when leaving work, Joe wants to let his partner know he has left and is on his way home; however, while attempting to the leave for the day, this task may get lost in the shuffle. This is why IFTTT is such an effective and useful tool, because it assumes part of Joe’s memory and allows him to focus on more cognitively demanding tasks.

However, the distributed cognition approach is somewhat limited in this example because it does not account for the emotional feelings of his partner. If Joe text messages his partner everyday when he leaves work, then his partner know would know he was thinking of them at the moment of the text. However, when this task is automated, Joe may not be thinking of his partner when the text is sent, and his partner may feel unappreciated by IFTTT’s automatic process. Thus, while IFTTT may make tasks easier by absorbing part of Joe’s cognitive load, there are potential emotional pitfalls, which are not accounted for by the theory.

Social Dimensions

The theory of distributed cognition states that we are able to distribute our cognition socially via interactions with others. Furthermore, distributed cognition takes on the role of analyzing cognitions when individuals act within certain environmental structures (Hollan, et al., 2000). When looking at potential IFTTT interactions, we find very interesting results, specifically, when analyzing how a group leader is able to interact with his team through the application.

When leaving the office for the day, IFTTT automatically sends an email to Joe’s team updating them for the next day. In viewing this action through a distributive cognitive lens, we first notice that Joe has electronically stored the team’s future schedule, which can be thought of as a cognitive task. The creation of the recipe shows that Joe feels it is important that each team member is on the same page and in the same mindset for the following day. Thus, in this instance, Joe is charged with creating the schedule and remembering to email his group the schedule for the next day. Joe is able to create a successful, and efficient, organization by using IFTTT to automatically inform his group of the specific tasks that need to be done each day.

Cultural Dimensions

Distributed Cognition also recognizes that our culture affects how we think and interact with everything around us. This means that our culture has a large influence on our thoughts and thus our interactions with technology. Hollan et al. (2000) mention, “Culture is a process that accumulates partial solutions to frequently encountered problems.” IFTTT is a great example of coalescing all of these “partial solutions” into one platform that relieves users' cognitive burdens in many different ways.

For instance, the garage light bulb and switch was an innovative technology that had an individual purpose at the time of invention (light at the flip of a switch). Now that light is controlled by IFTTT through an Internet-connected Belkin WeMo Light Switch, altering how we think and interact with the light, and changing it as a cultural artifact. Similarly, the ability for Joe to send a message to his partner, or for Joe to create a schedule and send it to his team were great innovations in their own right. However, IFTTT has transformed these seemingly independent technologies and interwoven them based upon the cognitive tasks Joe must accomplish when leaving work.

One of the potential disadvantages of culture is that it creates preconceived notions that may cloud our judgment when attempting to innovate (a light turns when I flip a switch, as opposed to a light turns on when I leave a certain location). IFTTT is an interesting example of overcoming such hindrances because it makes tasks that were once seemingly impossible, not only possible, but effective in integrating a user’s cognition with seemingly independent objects.

![]()

References

Hollan, J., Hutchins, E., & Kirsh, D. (2000). Distributed Cognition: Toward a new foundation for human-computer interaction research. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 7(2), 174-196. doi: 10.1145/353485.353487

Rogers, Y. (2012). HCI theory: classical, modern, and contemporary. Synthesis Lectures on Human-Centered Informatics, 5(2), 1-129.

IfThisThenTheory.com | An HCDE 501 Site